Željka Aleksić

In conversation with Barbara Pflanzner, Academy Studio Program, Creative Cluster, April 30, 2024.

In your artistic work you engage with questions of social class and capitalism and, coming from a working-class family, you reflect on your own position within this system. Could you share what motivated you to start studying art?

Indeed, I come from a working-class background, yet I perceive a shifting landscape where traditional class distinctions seem blurred. Instead, I observe a widening gap between the affluent and the disadvantaged, with the working class seeming less defined. In 2014, my brother Žarko Aleksić moved to Vienna to start studying at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, and our frequent conversations about life in Vienna and his experiences there ignited my interest. At this point, I pursued my artistic endeavors in Serbia, albeit only as a hobby. He suggested that I consider studying. He has been a pillar of support, believing in me even when I lacked faith in myself. While our entire family shares a profound connection, my bond with my brother is particularly special; he taught me everything about art. Thanks to him, I started to work on my portfolio and my application to the Academy. In 2017, I came to Vienna to take the entrance exam, with the intention of returning to Serbia afterwards to learn English or German and at the same time expand my artistic repertoire. Initially, I was drawn to photography due to my interest in new media, but Martin Guttmann remarked that my true talent lay in painting rather than photography. I was then invited to Ashley Hans Scheirl’s contextual painting class and Monica Bonvicini’s performative sculpture class. Discovering that there was a performative sculpture class was a revelation, but after a conversation with Ruby Sircar, I eagerly embraced the opportunity to study contextual painting.

You finished your studies in 2023 with Despina Stokou with your diploma project Das Kapital, in which you examined the economic prerequisites necessary to study art and which earned you the Academy Prize. How much does it cost to become an artist?

It’s very expensive. Now I feel equipped to talk about it because graduating has brought significant changes, both physically and mentally. If you’d asked me three years ago, I would have often described myself as a student rather than an artist because I didn’t feel like an artist. First of all, I identified as a student of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna who worked in a bakery but also other types of jobs, such as in a cafe, as a cleaner, or as a photographer. However, after I got my degree, I started presenting myself as an artist, because now I truly believe that this is true.

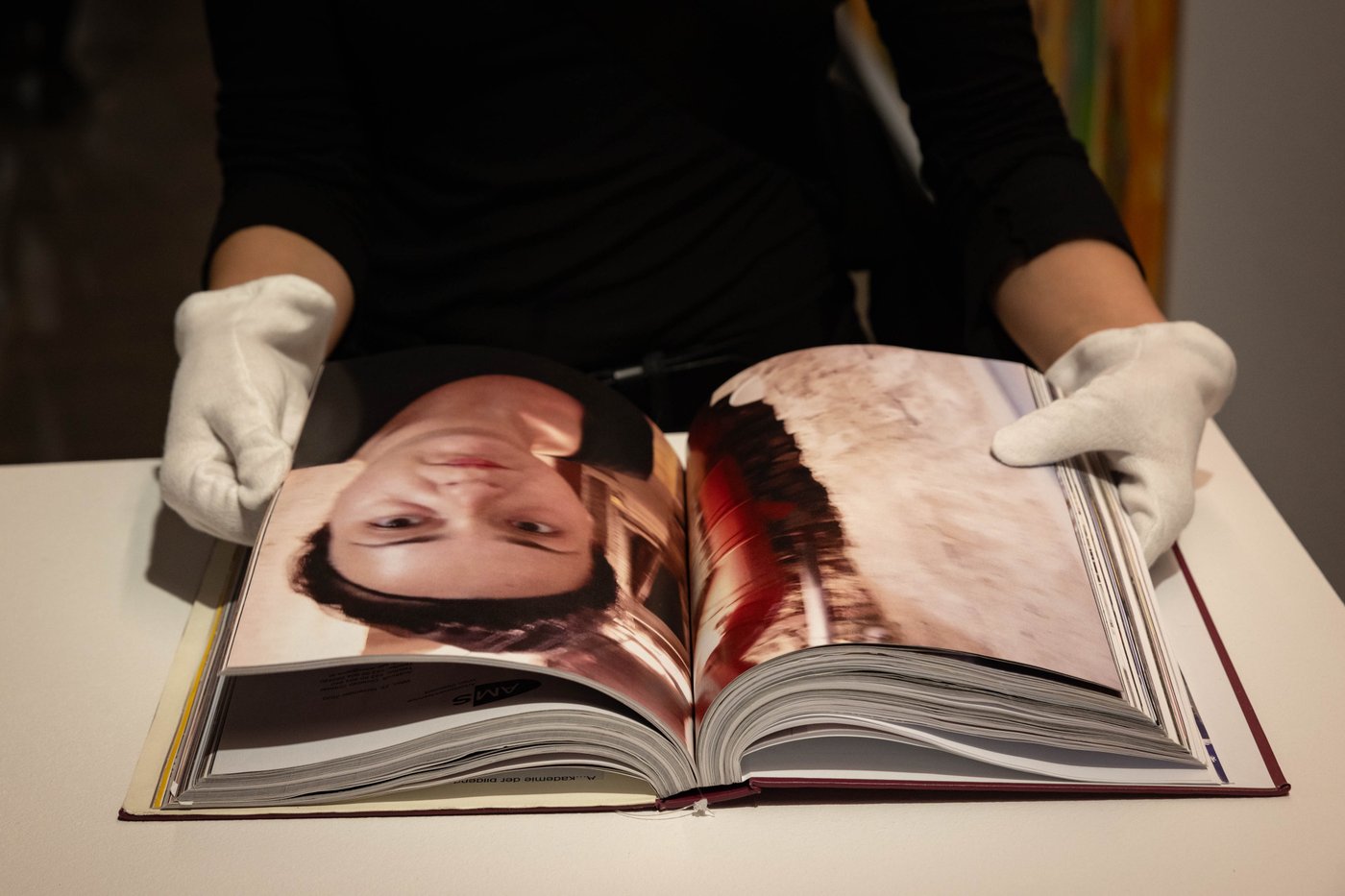

Das Kapital covers my journey from the moment I arrived in Vienna to the last day of my studies. The price attached to this book is 54,312 euros. This may seem excessive, but it represents my entire earnings during my entire stay in Vienna (and that income is actually spent on living expenses such as paying rent and all the things that are needed). I chose this value to encourage thinking about the true cost of becoming an artist. Is it solely in terms of money or is it also measured by experience? In today’s capitalist society, money often takes precedence. While I don’t want to equate money with ultimate fulfillment, I do recognize its importance in leading a comfortable life.

You have now transformed your identity into a new one as an artist. How does this affect you now?

Things have shifted slightly since obtaining my diploma because now I feel a sense of privilege. But when it comes to my legal survival, I have been fighting with MA 35 for six years about my position in Austria and have often faced discrimination in my applications. However, I believe that has changed a little, particularly after receiving the Academy Prize and having the opportunity to showcase my artwork at Kunsthalle Wien. It’s a different situation now, which has slightly improved for me. So I became visible as an artist but invisible as a worker.

This correlation, for instance, is evident in a piece created for the Vienna Museum, showcased in the exhibition Brotlos (Breadless). Could you share more details about this particular artwork?

At the very beginning of my stay in Austria, foreigners often mistook me for a Serbian artist who deals with war themes in my art. This misconception prompted deep reflection on my circumstances, as I felt unprepared to deal with such a sensitive subject. Despite coming from a troubled country, I lack direct experience with that particular topic. When the curator of the Brotlos exhibition approached me, I had already been working in a bakery for three years. The idea of presenting rye bread came to mind. Unlike in Serbia, where white bread prevails, here in Austria, rye bread has a cultural significance. I also did cleaning work in two apartments in the 18th district. I, personally, live in the 15th district, a predominantly immigrant area in stark contrast to the 18th district, where wealthier people tend to live. I have noticed that certain products at nearby Billa or Penny stores are equipped with anti-theft devices, unlike in the 18th district. So, I came up with the idea of making objects out of rye bread by putting an anti-theft device on them. While Vienna has repeatedly been voted the most livable city in Europe over the past decade, the cost of living has also risen enormously, while earnings remain the same. At least in my case. This installation aims to illustrate not only my daily work, but also the context behind it.

At Kunsthalle Wien you’re currently presenting three works, all of which deal with your daily life in a different way.

Exactly. In the exhibition at Kunsthalle Wien, I’m presenting three artworks: a performance titled GLEDAJ MAJKU, BIRAJ ĆERKU-KORENJE [Look at the mother, choose the daughter – roots], my piece Das Kapital, and a new work, Numinous Toy. The performance holds particular significance for me, as both my mother and grandmother are involved. Although I previously showcased it with my mother in 2019, I believe it to be better now, given my increased experience and the inclusion of my grandmother. I’m very happy about that because both women have been a great support throughout my life. The performance involves our hands, specifically our fingers. All three of us suffer from carpal tunnel syndrome, which, while biologically caused, is exacerbated by manual labor. The name of the performance name is inspired by a kitsch Serbian show from ten years ago. In this show, men seeking a relationship would go on dates with three mothers and, based on their interactions with the mothers, choose one of their daughters as a potential wife. I also show a sculpture featuring emerald green plush on one side, which is soothing for the eyes, and a bathroom on the other. The bathroom is a profoundly intimate space and it refers to beauty and self-care. This prompted me to start making drawings inspired by the strands of hair I lost. I wanted to juxtapose personal perception with an outside perspective on my own appearance. I have also incorporated a mirror into the installation, a component I consider essential. Coming from a small town in Serbia, where people are very curious, I find the mirror to be particularly poignant. Through the mirror’s reflection, I invite viewers of the sculpture to ask themselves, “Who am I, who are you?” – much like what I ask myself every day. In this regard, my artworks frequently take on a performative nature. When I started making Das Kapital, I thought about the ways in which our professional roles influence our self-perception and presentation. I realized that our external appearance often reflects the internal changes wrought by our occupations. This realization particularly struck me as I reflected on my own experiences. For example, while cleaning, I rarely thought about my career path; however, in interactions with others, especially in customer-oriented professions like the bakery service, presentation became crucial. It’s fascinating how different environments place different degrees of importance on appearance, influencing not only how we’re perceived by others, but also how we perceive ourselves.

In your hometown in Serbia, you established the Center of Culture and Arts K019. What does the center exhibit, and what is its primary focus?

Primarily, we introduced new media and photography, and were organized as a association. We started with a lot of enthusiasm, offering photography courses for the local youth and showing films. However, everything turned out to be a bit difficult and I limited my involvement. That’s why I’m not inclined to continue with this right now, as I prefer to prioritize my art practice, which I feel is more important at the moment.

After finishing two significant projects with exhibitions at Kunsthalle Wien and the Wien Museum, what’s next?

I have a lot of upcoming projects at the moment, which I see as a nice, positive change. I’m currently preparing a performance and an artwork for das weisse haus. I’m also going to Croatia to the VHV Academy, which I’m really looking forward to because it’s my first art residency. As of May 1, I’m officially transitioning into the life of an artist. Inspired by Mladen Stilinović’s work The Artist at Work, where he’s shown sleeping, I present the work The Artist at Rest. It feels like a vacation not working in the bakery, although of course I’ll be doing art work during the VHV Academy. Moreover, in May I’m traveling to Slovenia for an exhibition that is part of the Ljubljana Art Weekend.