Nils Frederik Neuböck

In conversation with Barbara Pflanzner, Academy Studio Program, Creative Cluster, March 19, 2024.

You studied architecture at the Academy and worked on projects during your studies that are becoming increasingly important in lieu of climate change. What topics are these?

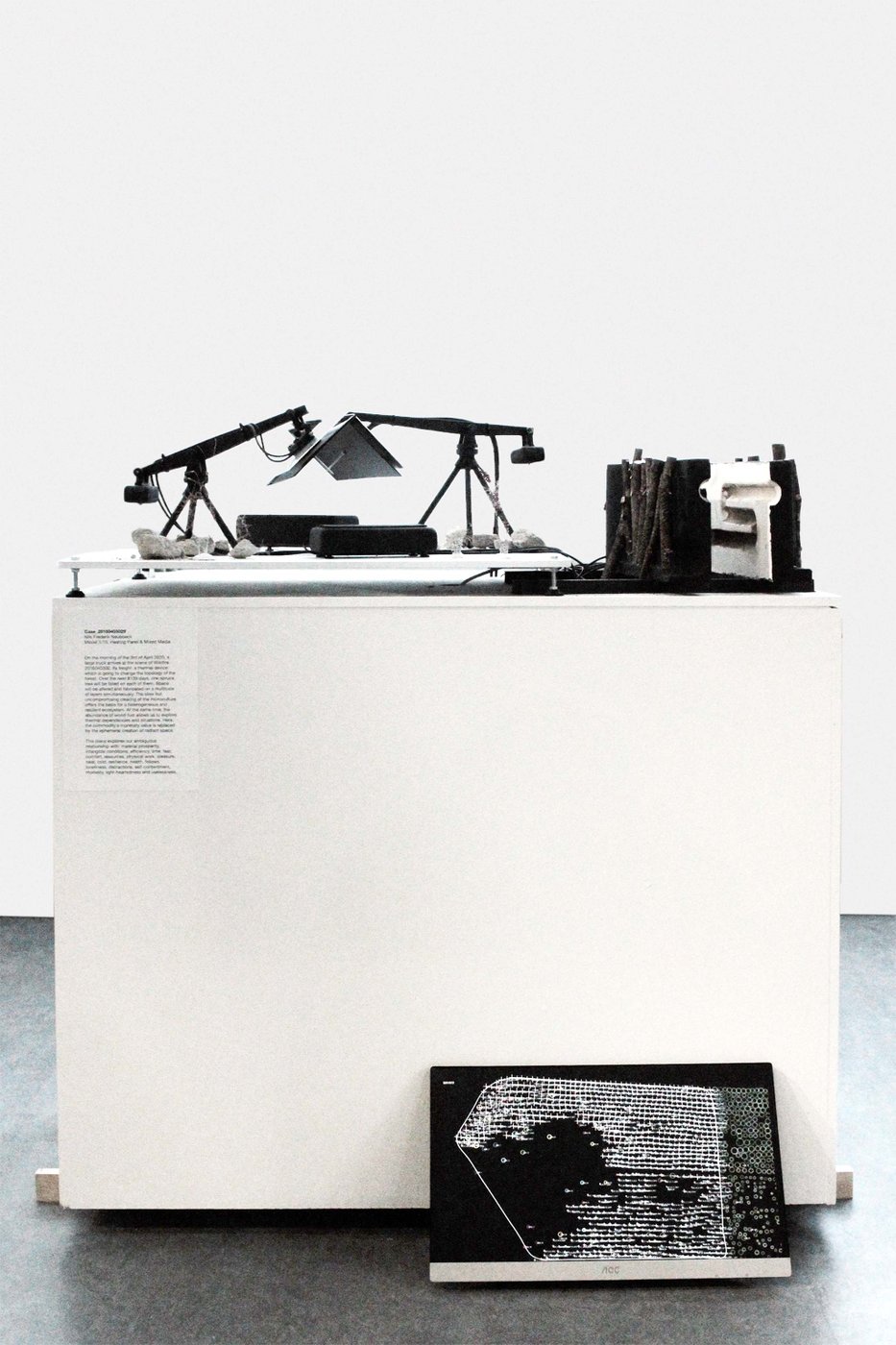

Yes, you’re right. During my master’s studies, it became clear to me that I wanted to focus on how one deals with climate change. As part of the year project by the IKA [Institute for Art and Architecture], Hitze Takes Command (2020/2021), for example, I proposed a concept for living in the forest with just one stove while simultaneously transforming an unstable spruce monoculture into a climate-resilient landscape. The idea was that every day, a spruce tree would need to be felled, and only the amount of energy from this tree would be available as a limited energy resource – a “Lumberjack in Residence” program, so to speak, allowing interested individuals to experience a different approach to normative comfort and a deeper connection with themselves. Whether this would work in reality or not could only be determined by trying it out. The starting point was that architecture no longer needs to be an enclosed space, as we know it in Central Europe, but living areas are gradually opened up, with heat generated, for example, around a stove. In other words, if I’m closer to the source, it’s warmer, and if I’m further away, it’s cooler. This raised many questions – about comfort, meaningfulness, potential benefits, sensory experiences, connection to nature, and how urban dwellers, in particular, can experience nature. If I’m sitting in a closed room and it’s raining outside, I don’t notice it. But if I open the window, I immediately feel a certain connection to the outside space and can react to the weather, nature, the smell, the noise, or the chirping birds. These considerations were the starting point for several projects that I explored up to my diploma, on various levels but always raising the same questions.

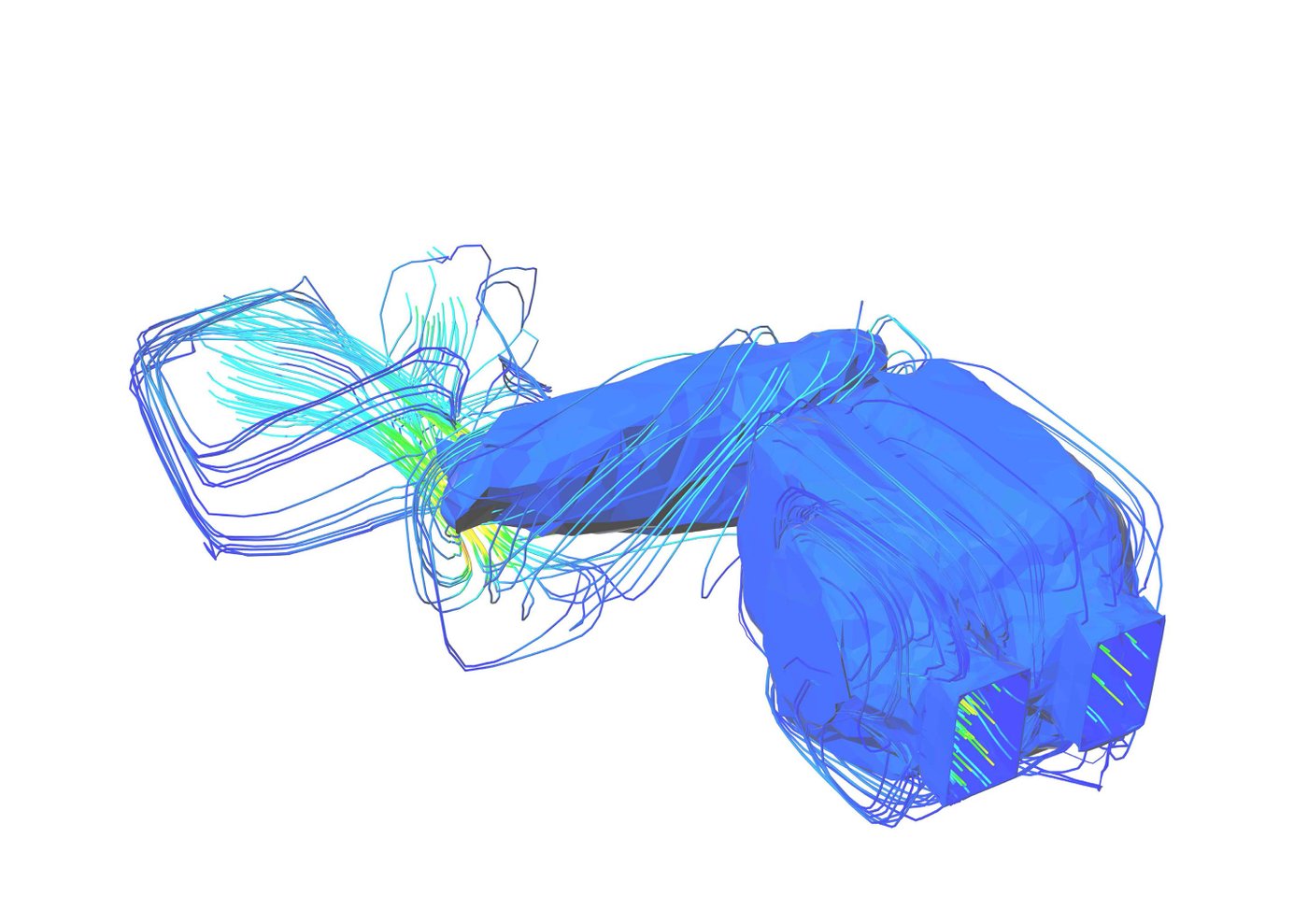

Two of these projects are Against Worldlessness (2021) and your diploma thesis Report from Outer Space (2021/22), in which you explore the possibility of a geothermally activated landscape in which architecture no longer has or needs a shell. What exactly are these two projects about? And what is your view of architecture in this context?

Against Worldlessness illustrates a kind of commune, a community of people willing to live outdoors together for a certain period. The school built by Helmut Richter on Kinkplatz in Vienna’s Penzing district was due to be demolished, and to prevent this, the new concept proposes to activate the building using geothermal energy, making it usable again without significant changes to the existing structure. The theory is that many buildings could be adapted and saved if its users were willing to accept, for example, that the temperature or humidity inside is not always constant and there sometimes may be a slight draft. I believe that greater resilience and adaptability on the part of building users would open up new and exciting possibilities in architecture. How we live and build is ultimately a cultural matter. The Japanese climate, for example, is milder than ours, but not fundamentally different. Nevertheless, the Japanese have a completely different approach to openness in architecture, such as with shoji – walls made of paper. The question is: Do we always have to continue as we currently do? Or would it be more advantageous for climate and environmental reasons to rethink what we are doing and perhaps even strive for a certain cultural change? My impression is that a lot of research is currently being carried out in CO2-neutral construction, recyclability, energy optimization and passive house standards. This is important, but at the same time it always presupposes that we don’t actually want to change our behavior. Or rather, we are increasingly isolating ourselves from the environment because houses are becoming more and more hermetically sealed. In this sense, I’m less interested in improving the architecture than in encouraging people to initiate cultural change or to question whether the way we shape our daily lives necessarily has to be the way it is.

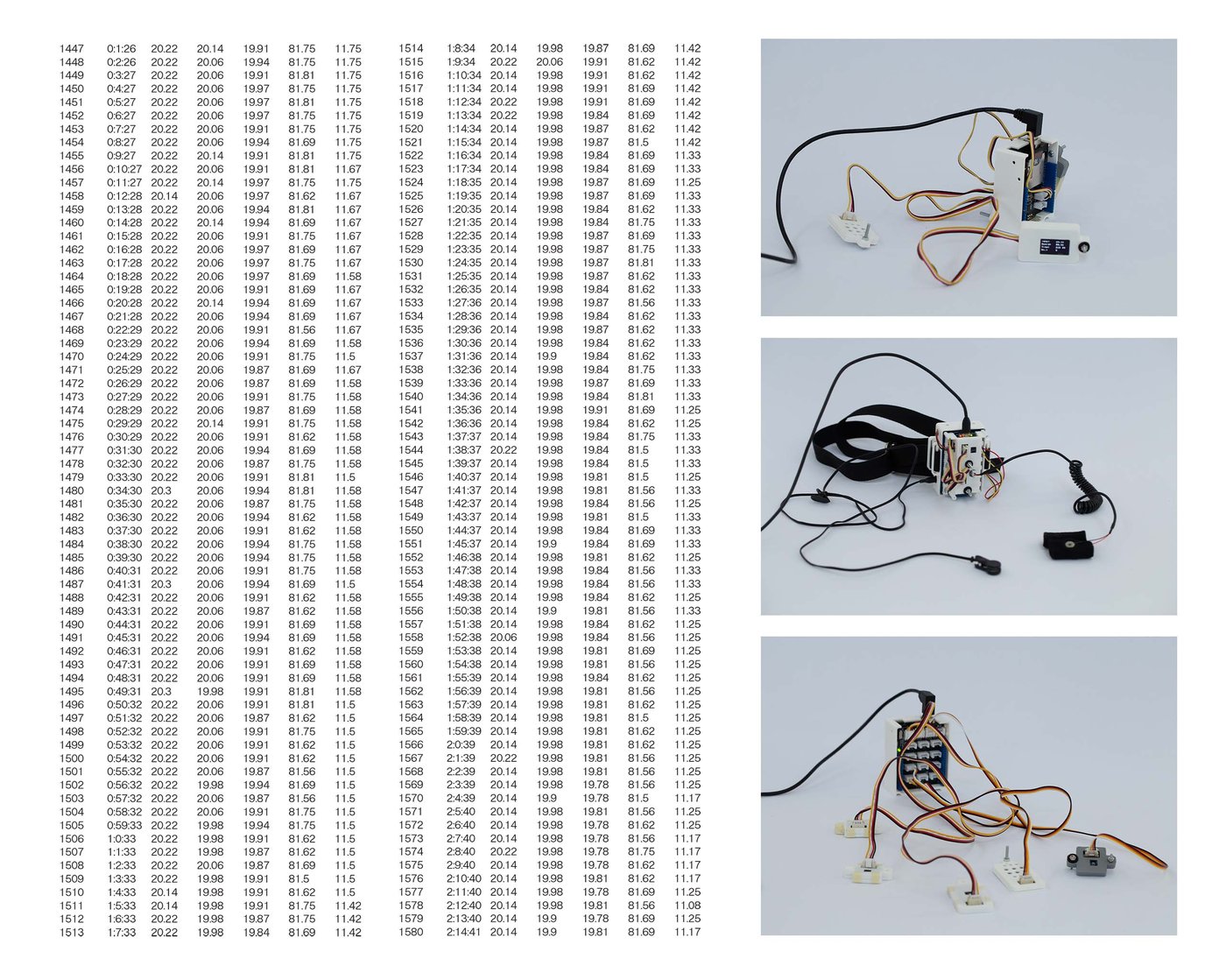

In the project Ways of Knowing (Myself), you examine how a body relates to its environment. How did you analyze this topic, and did your research yield any results?

This project attempts to investigate and document the ambivalence between empirical data and highly personal experiences. For example, I installed a sensor inside and outside my window that continuously measured the temperature. The almost invisible pane of glass in between makes a fundamental difference. This is logical, but once you consider that there’s a difference of 15 or 20 degrees outside and only one or two degrees inside during the daily cycle, it becomes visible and describable. In these studies, my aim was not so much to achieve an empirically precise result, but rather to demonstrate, also through my own body. For example, I measured the temperature on various parts of my skin after doing something specific or being exposed to a certain environment.

Is this also a theme that came into play in the project Studiolo (My Body Has Become a Heat Exchanger)?

Yes, Studiolo – a term used to describe a room dedicated to study and artistic engagement – was ultimately the amalgamation of these two aspects. Studiolo was inspired by the traditional Japanese kotatsu – a table with a heat source underneath and a thick blanket on top – which allowed me to work and rest outdoors. The table stood in the courtyard of the Academy for about three months over the winter. I spent several evenings and nights there. The idea was to measure the temperature of the environment one is exposed to while working or contemplating at the kotatsu and to describe what one feels. This juxtaposition is interesting because what the sensors describe can ultimately mean anything. If another person sits there, the data might be identical to mine, but they feel completely different. If it’s cold outside, you usually go indoors quickly to get warm or, conversely, when it’s hot outside, you seek a cool spot. With Studiolo, you have warm feet but a cool head. Ultimately, you become a heat exchanger yourself.

At the beginning of the Studio Program, you had planned to make your personal archive visible on your website or a blog and to work towards possible self-employment. You’re currently also working in a Viennese architecture office. How are you progressing with these plans?

Yes, exactly, I’m still working on that. My involvement in the architecture office is very intense at times, which sometimes makes the day too short for everything I want to do. The website is currently under construction. I’ve also been working on my projects for it, especially my diploma. For me, the studio is a bit like an extended living room. I live just around the corner, so I can come here with my slippers. I’m trying to find a counterbalance to office work on the computer. That’s why I’m trying out more handicraft work again, because you simply have the opportunity to do so here. Besides, I recently submitted a concept for a competition and am currently working on another project submission. I’ve always had the idea of developing a project for art in a public space that provides a social meeting point in the city during certain times of the year, similar to a tiled stove in winter or a cool shade provider in summer. I experienced this once during a work stay in Lisbon, where it was extremely cold in our office, and we had to work with jackets and hats on. At some point in December, our boss put a heater in the middle, and we always gathered around it during breaks and drank coffee, which made communication much better. Such moments show that social events can be encouraged by unusual circumstances.

There’s currently an object in your studio that seems to consist of individual parts of a pipe – what is it?

Right now, I find the topic of stacking interesting. These paper rolls were originally intended as formwork for a concrete column. Concrete columns are actually a very rational element; they come in all sizes – you set up the formwork, pour in the concrete, and it’s done. I found it interesting to ask what it means nowadays if you move away from this rationality a little: where could you end up? As I tried to store or simply place the individual parts, I realized that it’s not that simple. I then tried to make connecting elements and realized that it’s geometrically extremely complex. If you want a part to be slightly twisted, it immediately becomes difficult because it’s twisted in all directions – that’s a geometric problem. In this sense, I’m trying to find approaches that could perhaps be reused elsewhere. Here in the studio, I’m practicing a bit of free thinking about things I otherwise wouldn’t have time for or wouldn’t be able to do.