Ella Steinbach & Xandi Vogler (Lex Hymer)

In conversation with Barbara Pflanzner, Studio at Creative Cluster, May 24, 2023

Together with your colleague Selma Lindgren, you implement projects as the group Lex Hymer. What’s your approach?

ES: We like to refer to ourselves as a three-headed stage and costume designer. There are three outgrowths that converge into one thread. Even though we don’t work together as a group on a project at the same time, Lex Hymer stands above it all. In theater, you always work collectively, but we start our collaboration right from the stage and costume design concept, which allows us to connect projects with each other in a broader sense. What I appreciate about our collaboration is that authorship is undermined: there is great trust and freedom for an original idea to evolve through passing it within the group. Under the name Lex Hymer we step back as private individuals and present ourselves as a group in our work.

How should one imagine your collective work?

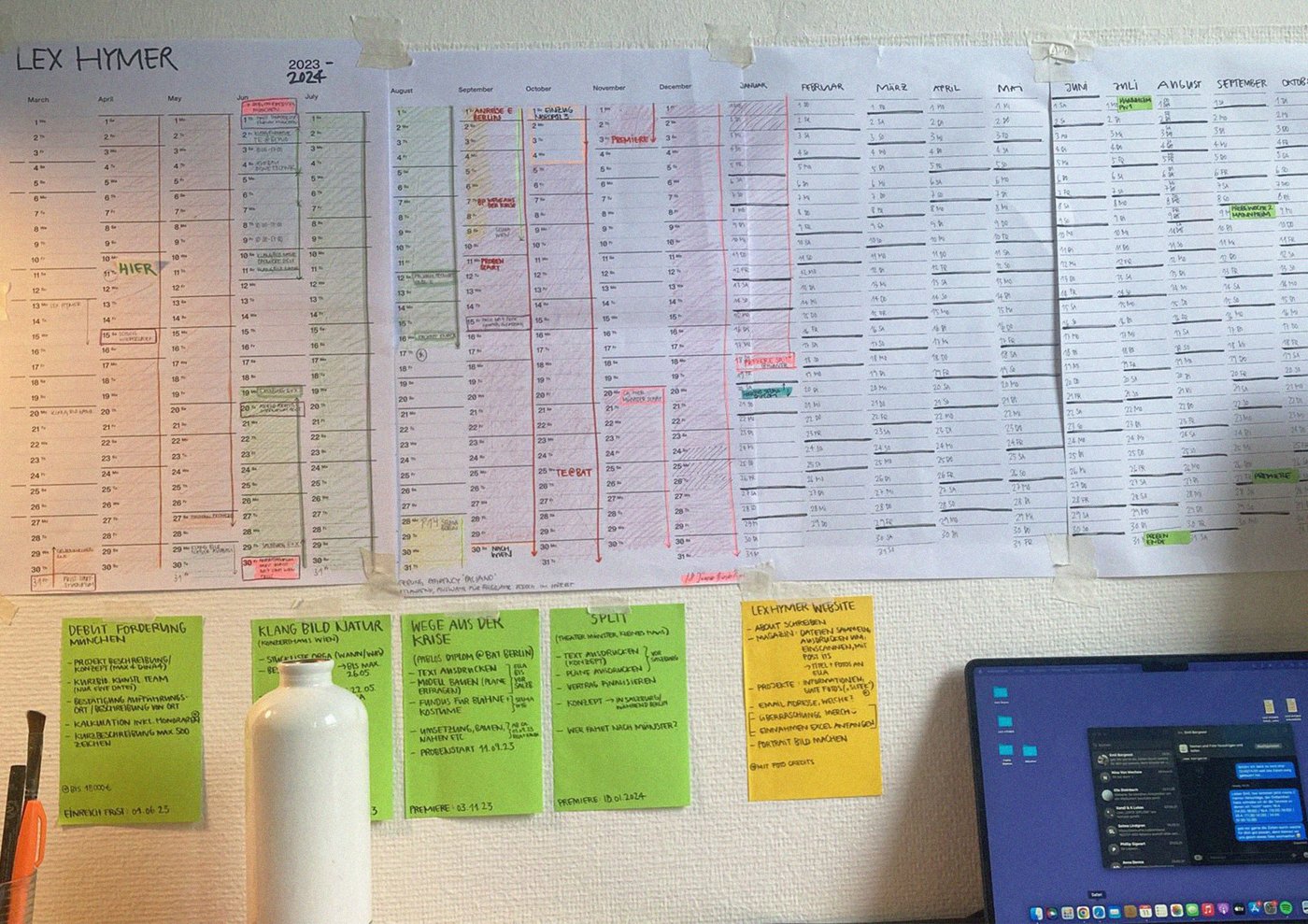

XV: Working in stage and costume design is incredibly diverse, with many different tasks in the process, starting from initial conversations, the design, followed by workshop submissions, rehearsals, and finally the premiere – sometimes spanning over a year and varying in intensity. We’re currently working on four projects simultaneously, each at a different stage of development. For example, during the design process – which I would say is the most intimate phase of a project – you can’t simultaneously work at the theater and attend rehearsals. That’s why we’ve created a mode that allows us to pass things on to each other and adapt tasks according to our needs and capacities.

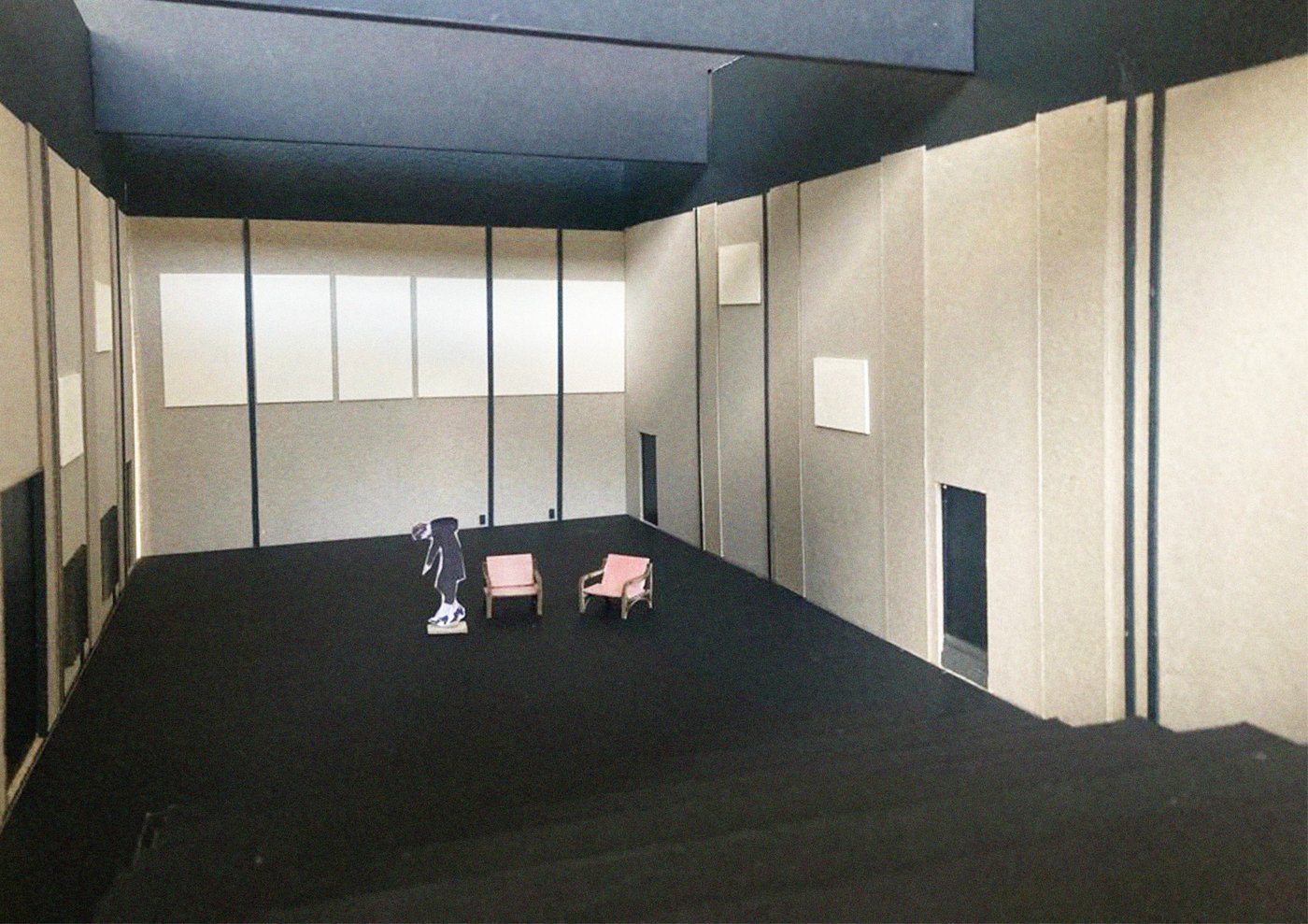

ES: These different work phases also require different conditions. In the design phase, one can theoretically work from anywhere, but during rehearsals, costume fittings, workshop discussions, or set rehearsals, one needs to be present on-site. That’s when the set is sketched in a one-to-one-scale 3D model for the first time, to check if the dimensions, measurements, and perspectives correspond to what we envisioned.

XV: Our profession involves a lot of traveling; we are often on the road for several weeks to months. When we’re at the theater, we often work 14-hour days: in the morning, we have fittings, and from 10 a.m. scenic rehearsals, with workshops in between. In the evening, we continue rehearsing until 10 p.m. or work on lighting the set. Afterwards, we usually sit in the cafeteria with the director and discuss the next day’s rehearsal. Such a rehearsal process can be both energy- and responsibility-intensive, but at the same time, it can be exhilarating because you completely immerse yourself in the world of the play. What you read in the theater text or libretto beforehand becomes far from fiction. After the premiere, you sometimes need a longer break to regain your strength. It’s nice that Lex Hymer makes that possible for us too.

And how do you organize yourselves among yourselves? Do you regularly meet here in the studio, and will there be a place where you can come together after the end of the program year?

ES: It’s nice that you ask us that, because the Studio program has strongly encouraged this exchange. In our applications, we emphasized that we would benefit the most from the scholarship if we all received it, and we’re happy that it worked out. The studio became a fixed meeting point. When we’re not all in Vienna at the same time, we communicate a lot via Messenger, Google Drive documents, or Zoom. When we move out of here, we’re going to move into another group studio. It will be a shared workspace for stage designers where we’ll work at different stations, and ideally, one can always catch up on the current status of each project.

As a group, you consist of three women. Do you have a feminist approach in your work or in the projects you choose?

XV: As a female trio, we’re incredibly supportive of each other and try to support one another. Work in set design is still better paid than work in costume design, even though it’s equally labor-intensive and requires the same level of expertise. This is probably because set design is still a male-dominated field, with men usually working with other men, such as production designers, stage technicians, constructors, locksmiths, carpenters, and others. Additionally, the budget allocated for set design is often greater than for costume design. In a way, with Lex Hymer, we’re developing a strategy to overcome this issue: we combine both aspects, pooling the entire budget for set and costume and decide where to focus our efforts. So far, this approach has worked wonderfully.

ES: The production of Tschick, for which we designed the set at the Vienna State Opera, is the first opera we’ve been involved in where the female lead’s motivation on stage is not solely based on being loved by a man. She has her own reasons. It motivated me greatly to contribute to the realization of the piece because I could also get behind it thematically, and I was proud to showcase the project. There’s still a lot to be done in opera compared to theater, and we’re glad to have been approached for projects like this.

XV: At the same time, the question of a feminist approach is important to us, not only in our collaboration. Especially in costume design, you have to be totally mindful how you want to portray people on stage and deal with the topics of body and representation; you need to be extremely mindful. This includes not only a feminist attitude but also cultural appropriation and racism. Costumes often employ binary coding or resort to discriminatory character representations. We strive not to rely on stereotypes in our work. Our collaboration is incredibly helpful in this regard, as we can critically question each other and our choices.

Which project would you consider as Lex Hymer's first project? On your new website you also list earlier, individual works.

ES: I would say the first Lex Hymer project was Tschick at the Vienna State Opera, even though we didn’t have a name at that time. The name came about only last year in September when we wanted to professionalize as a group. We thought it would be interesting to include individual works that were created before Lex Hymer on the website because we always talk about our “cosmos,” and certain elements reappear in different forms in other works. Sometimes, you carry ideas within yourself, which may have remained theoretical during your studies but can now be realized due to resources and infrastructure. This creates a catalog of things for which the right piece will eventually be found – every idea needs the right puzzle piece. That’s why you can browse through the Lex Hymer website like a magazine. We also want to keep the range of our work as broad as possible, since we all contribute different expertise and preferences.

Did you face any challenges with Tschick, considering it was the first play that was realized in a large theater?

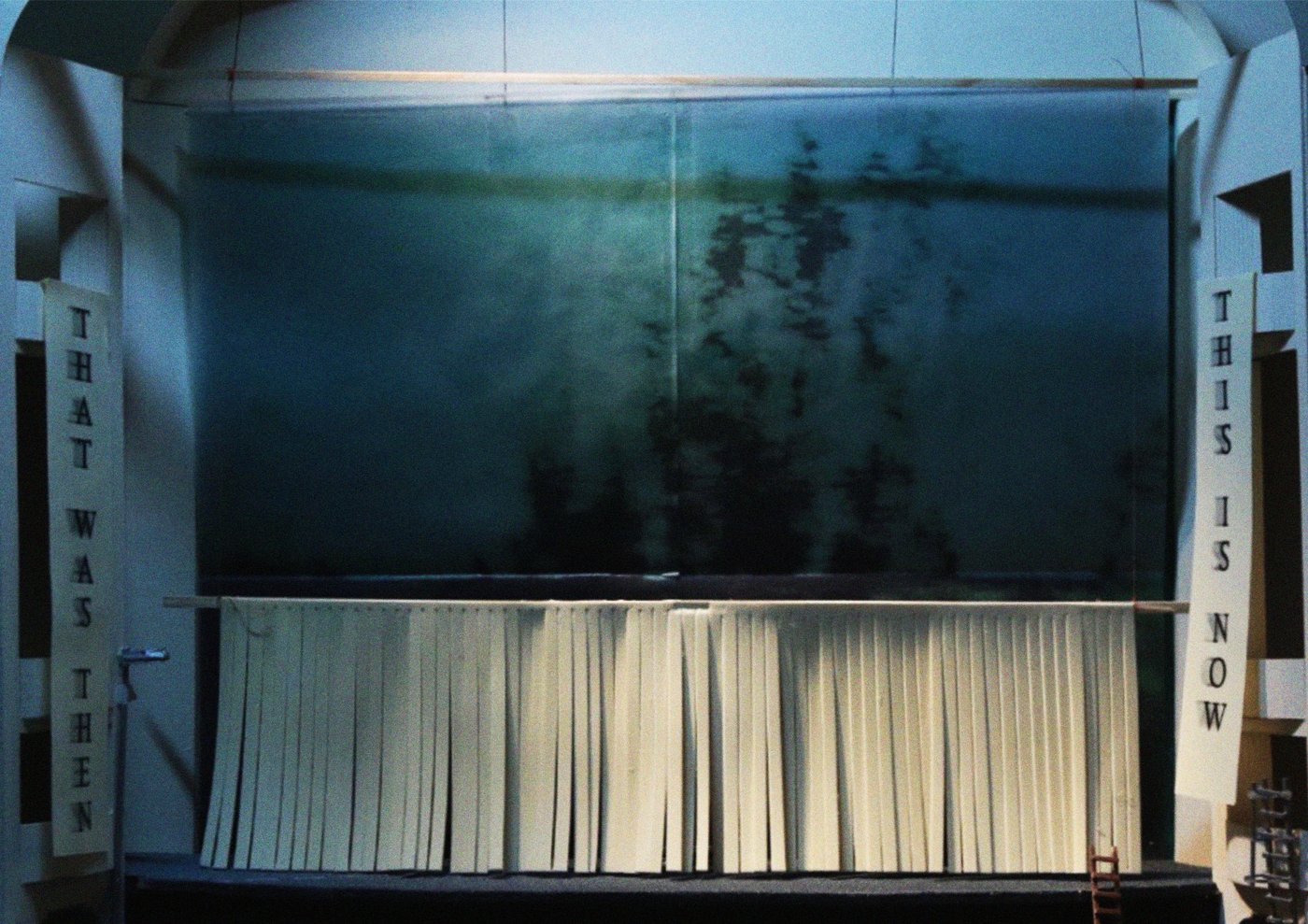

ES: Tschick is a youth opera based on the well-known novel by Wolfgang Herrndorf, in which two boys embark on a road trip, experience various things, and come back with great insights. We covered the Iron Curtain with a backdrop – a large stage painting – and the play was performed in front of it. That’s quite interesting, because the Vienna State Opera has such a busy performance schedule that they plan shows that take place only in front of the Iron Curtain, allowing the stage sets behind it to remain intact. That was the first challenge, implementing a design on such a narrow, almost runway-like stage. Tschick was an attempt to stage an opera for young people by young people. The adult roles were played by ensemble members of the State Opera. It was a truly wonderful experience for our first major production, which started quite quickly, just two days after our final diploma performance.

What aspects that are important to you in your work reappear in other projects?

ES: We actually started delving into theater painting and the questions that come with it, such as the (im)possibilities of representation in theater, during our diploma. This question has been a recurring theme in many of our projects. For example, in Tschick at the State Opera, as I mentioned earlier, we covered the Iron Curtain with a large backdrop curtain. The idea was to create the feeling of looking out of a car window and seeing a landscape pass by. And in Der Mensch erscheint im Holozän (Man Appears in the Holocene) in Gelsenkirchen, we designed a circular horizon that served as the support for an abstract mountain panorama painting, referencing the setting in the play.

XV: The enthusiasm for craftsmanship and the many artisans who come together in theater is also a leitmotif in our artistic work. We’re fortunate that such productions have numerous talented craftsmen and artists supporting us: our backdrops are done by theater painters; there are carpenters and locksmiths; in costumes there are wardrobe masters, milliners, shoemakers, dyers, and makeup artists – we greatly appreciate that. We try to consider this in our designs, focusing on creating something custom-made or modifying existing elements, rather than ordering costumes from online retailers like Zalando. We’re always searching for translations and ways to avoid simply illustrating the play one-to-one, thus avoiding tautologies. It’s important to us that the space and costumes are equal participants in a play alongside the performers. Additionally, there’s always the potential to transform the stage. We think of our stages in a sculptural way, and in the design process, we’re not far from sculptural work. However, compared to visual art, it’s a tremendous opportunity to invent more than just one image over the course of an evening. I believe these, along with a distinct visual style, are motifs that have characterized our stages so far.

For your thesis, for which you won an honorary prize together with Lukas Kötz, this collaborative approach that you mentioned at the beginning was tested for the first time.

XV: Our thesis, titled Ich bin das eine und das andere bin ich auch (I Am the One and Also the Other), revolved around the question of how theater can bridge or even counteract the gap between human and non-human earth inhabitants. The work also examines how the (im)possibilities of theater can shed light on the act of seeing and being seen, as well as the question of what is culture and what is nature. We also performed in the piece ourselves, which meant that we took turns directing. None of us ever saw a full rehearsal because the person who watched and took on the directorial role had to mentally fill the gap left by their absence. In the end, a kind of ping-pong game emerged among the three of us, and it became difficult to differentiate whose idea originated from whom. We managed to utilize the different expertise we each have among the three of us. The form in which we worked ultimately led to an intellectual exploration: our boundaries, our disciplines dissolved, which was also the theme of this thesis. This is something we want to continue with Lex Hymer.

ES: One of the most beautiful aspects is that so many friends contributed to the production. That played a significant role in enabling us to create something so big. And because we worked on the thesis as a trio, we could always support each other. We painted the scenic backdrops ourselves, devised and technically implemented their installation, wrote the text, and made flyers and program booklets because our goal was to take it seriously and execute it as professionally as possible. At the same time, it was equally important for us to establish a work structure that was productive, enjoyable, and made everyone involved feel comfortable. I believe we managed that quite well, and looking back, the diploma is still my favorite project.

In May 2023, you designed the set and costumes for a performance based on the story Der Mensch erscheint im Holozän by Max Frisch at the Musiktheater im Revier in Gelsenkirchen. What is the play about, and what was important to you in designing the set and costumes?

XV: The story Der Mensch erscheint im Holozän actually hardly has any active plot. It revolves around an old man, Mr. Geiser, who’s alone in a hut in the Ticino Alps when the slope is about to slide; it has been raining for days, and the post bus is no longer operating due to the storms. In a kind of frenzy, Mr. Geiser begins to transcribe and cut out knowledge from encyclopedias and stick it on the wall. One could ask this question: If the landslide wiped out Geiser, who represents humanity, what would remain of humans? A central sentence in the book is “Nature knows no disasters; disasters are known solely to humans.” This theme naturally reflects current issues such as climate change or the questionable dominance of humans on earth. In our production, the story of Mr. Geiser was told on stage by seven performers in a retrospective manner – as if they had arrived from the future at the location and were trying to explain who and what had been there before them.

The set design emerged from a museological exploration. We worked here in Vienna and went to the Natural History Museum with [the play’s] director Pablo Lawall. Most of what is exhibited there existed long before us and will exist long after us. A museological representation connects well with the question of how to depict something in theater without it appearing in a natural way. We pondered the fact that people don’t really look at the stones in front of the Natural History Museum, but they do look at the stones in the museum’s display cases. In the end, we chose the diorama, which already has a highly scenographic quality. Our set design can be understood as a fragmented, shattered diorama. We specifically referenced the individual elements from the diorama but distributed them as props across the stage: there’s a painted circular horizon, an elevated platform that’s like a stage within the stage, museum benches, a stone that breaks out of the wall, and numerous other props. With the latter, we were interested in what is worth exhibiting and in the handling of everyday objects – “the things that surround us” – through which people ultimately tell their stories.

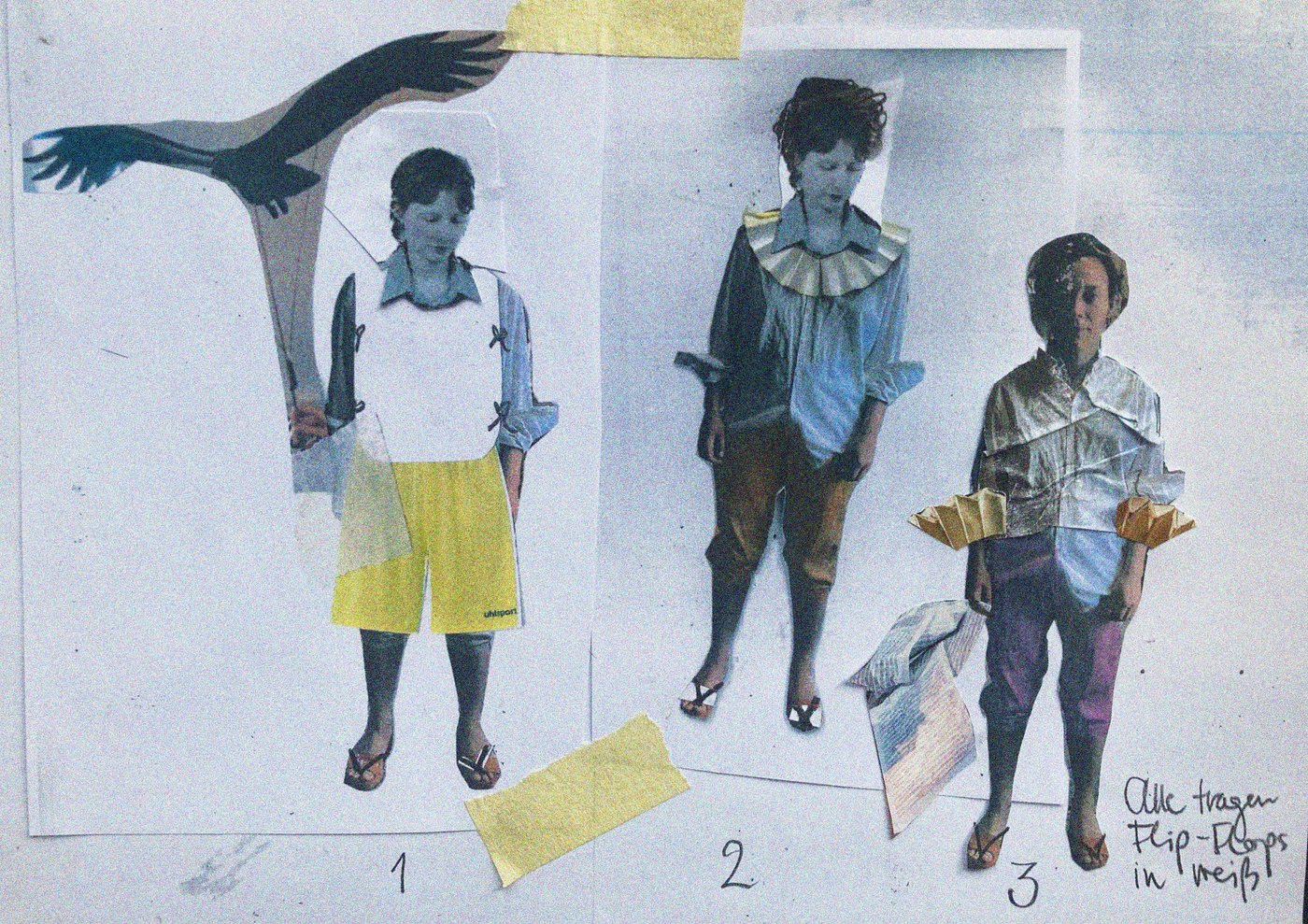

Working on the costumes was a lot of fun, especially collaborating with the workshops. Firstly, the theater had many great fabrics and a costume collection, so we didn’t have to buy very much and could work with what was already available. Similar to with the set design, we asked ourselves fundamental questions about nothing less than ourselves as humans on this planet and ultimately decided to perceive our performers as a delegation of non-human creatures who dress up as humans, or as they imagine humans would dress. It was interesting to question and deliberately misunderstand “our” way of dressing. The beauty was that Pablo Lawall incorporated these alienations into his directing as well.

Since you always work on multiple projects at the same time, what’s next on your agenda?

ES: Our next project is a concert titled KlangBildNatur at the Vienna Konzerthaus, which will premiere in early June 2023 and is aimed at children aged eight to twelve. We collaborated with set designer and director Philipp Lossau, whom we got to know during our studies, and the Young Masters Ensemble of the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, who will perform music that is inspired by nature. Together with Lina Eberle, we’re responsible for the set design and costumes. What’s interesting about this project is that we get to incorporate scenic elements into the concert genre, which usually has clear scenic structures, and invent a story to accompany the music.

XV: In November is the premiere of a play at the bat-Studiotheater in Berlin – the model is currently here in the studio. On January 18, 2024, is the premiere of Split by the author duo Sokola/Spreter at the Theater Münster, with whom we’re collaborating again. Pablo Lawall will direct, so it’s the same team as for Der Mensch. We’re also starting to think about a concept for another premiere by Sokola/Spreter in Mannheim for the following season, but fortunately, there’s still some time until then.